Major Projects

Jump to:

- Dissertation: Modernist Fiction and the Politics of Federation, 1880-1980

- Digital Humanities Project: Modernist Correspondence Networks

Dissertation

Overview

“One World, One Life”: Modernist Fiction and the Politics of Federation, 1880-1980

Writing in Paris at the height of the U.S. Civil War, the French politician and anarchist philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon predicted that “the twentieth century will open the age of federations.” His prediction took on new and suggestively figurative dimensions almost two decades later, when Virginia Woolf’s father, Leslie Stephen, adapted the idea of federation to the “microcosm” of mental order and individual “constitution”:

Man, in fact, is a microcosm as complex as the world which is mirrored in his mind; he is a federation incompletely centralised, a hierarchy of numerous and conflicting passions…. He is in some sense a unit, but his unity is such as to include an indefinite number of partly independent sensibilities…

Thought it may seem an incidental figure of speech, Stephen’s reference to federation took place at the outset of a transatlantic debate about the historiography of the British Empire and the future shape of state sovereignty. His metaphor of a federated self serves as an emblem of the overlapping literary and political concerns I explore in my dissertation, which describes how five modernist writers participated in the emergence of federalism as a mode of governance and structure of feeling. Examining the lives and writing of Oscar Wilde, Virginia Woolf, Jean Rhys, William Faulkner, and Salman Rushdie, I argue that their experiments with life narrative respond critically to “the age of federations” as it unfolds, enabling readers to sense—and potentially to shape—the changing constitutional arrangements of modern states.

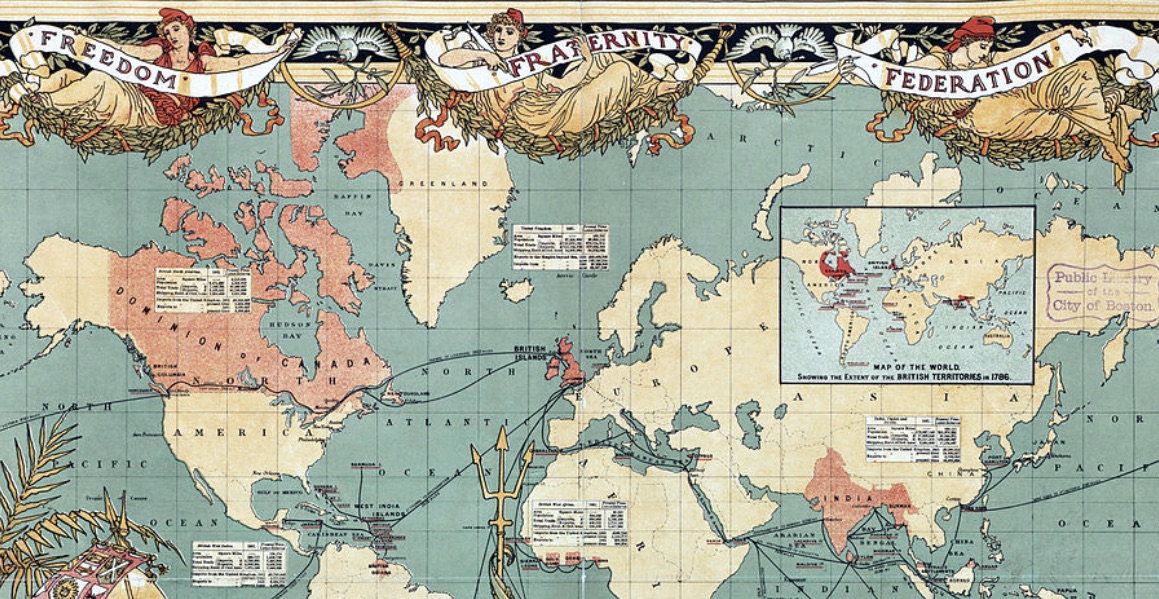

Fig. 1. Imperial Federation Map, 1886, from the Boston Public Library

Today, as more than 40% of the world’s population lives in states that are, or claim to be, federations (not including interstate organizations such as the EU), scholars in a variety of disciplines are reexamining the global history of federalism. My research places modernist texts at the center of this inquiry by considering their status and effects as constitutional narratives—narratives that revisit the origins of particular social relations in order to develop new perspectives on the present moment. Critics typically view literature’s relationship to the state with suspicion, whether because of the state’s protection of dominant interests or because they find it to be ultimately less important than other systems of order and exchange. I emphasize literature’s capacities for representation, in materially salient and politically transformative ways, particularly through its challenging of conventional images, attitudes, and narrative forms. I suggest that modernist fiction’s difficulty has to do with not only altering perceptions of the past but bringing contested histories to bear on the future of those abstract social and conceptual forms we sometimes refer to as government. In particular, I show how modernist fiction articulates the division of nation and world by what W. E. B. Du Bois described as “the color line.” For along with ideals of liberal citizenship and federated unity, the twentieth century was also an age defined by what Edward Kamau Braithwaite refers to as “negative federation”: that is, unification with and through apartheid.

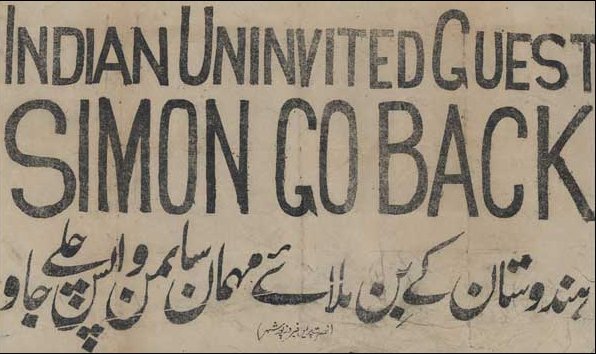

Fig. 2. Simon Commission Boycott, from the BBC’s Indian Independence Posters archive

Each chapter in the dissertation pairs a modernist writer with an important moment in the global history of federalism, using this context to develop a close reading of one of their novels. Chapters one and two bring new biographical and historical material to bear on Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) and Virginia Woolf’s Orlando (1928), which in dialogue with the U.S. Civil War and debates about Irish and Indian self-determination, offer contrasting views of imperial history from the vantage point of cosmopolitan London. Chapters three and four consider the discrepancy between metropolitan and and colonial views of federation by turning to Jean Rhys’ Voyage in the Dark (1934) and William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! (1936). These narratives challenge the ideal of political union based on racial sympathy by depicting young white protagonists who flee southern plantation economies but are unable to integrate into northern cities. The dissertation ends with a chapter examining the role that “loose federalism,” as the narrator of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1981) calls it, played in the decolonization and partition of India, now the world’s largest federal democracy.

Topics

- Modernist Fiction

- Constitutional Narratives

- The Bildungsroman

- Imperial History and International Politics

Research Notes

- Slides from my presentation on “the age of the Wilde picture” at Forgotten Geographies (London):

- Slides from my presentation for the “Global Modernism and Civil War” panel at MSA 17 (Boston):

- CFP for that MSA 17 panel, “Global Modernism and Civil War”

Modernist Correspondence Networks

Overview

I’ve been working with the Twentieth Century Literary Letters Project since 2012, when I took a course in Digital Humanities Databases at the Digital Humanities Summer Institute (DHSI). My projects in this regard have focused on assembling and visualizing the correspondence networks of Virginia Woolf, for example in this poster presentation at the 2013 Modernist Studies Association conference. I’m excited to be directing new energy toward this line of work in the following year, with the help of a fellowship and interdisciplinary Digital Humanities seminar sponsored by the Boston University Center for the Humanities (BUCH). I plan to explore data models and open source platforms for collecting and sharing linked open metadata about modernist letters.

But why “digital humanities”? Why correspondence networks?

Early in my degree program, I became fascinated with the collections of fan mail received by Virginia Woolf. This material was made accessible to scholars through excellent print-based editorial work by Anna Snaith, Beth Rigel Daugherty, and others (see also Melba Cuddy-Keane’s discussion of a few additional letters, and Sybil Oldfield’s collection of letters received posthumously). For me, the patterns of mutual influence recorded in some of these letters opened up alternative models of sociality and literary reception, relationships characterized by contingency and anonymity rather than intimacy or intentionality. They also didn’t fit with one of the most common frameworks for writing literary history: metaphors and social networks centered on the family. In an early paper presented to the International Virginia Woolf Society, I used a combination of queer theory and conventional close reading to describe these features in Woolf’s fan mail and to explore her connections to common readers and writers across the British Commonwealth and imperial diaspora.

However, I came to realize that my approach to these letters seemed to reinforce certain assumptions about interpersonal communication, self-possession, and inheritance. The archive where many of these letters reside is named after the house Virginia Woolf shared with her husband, Leonard Woolf, and, like the archive, I was continuing to use “Virginia Woolf” as an organizing principle for collection and interpretation (see Fig. 3 below). By reading these letters closely, I was positioning myself between Woolf and her readers, in effect trying to recover or stage a moment of mutual connection and understanding. To understand contingency and anonymity as structural features of the relationship named by the popular expression “fan mail,” I needed a more distant, depersonalized perspective—perhaps a less humanistic method. That realization led me to begin exploring various methods of social network analysis and visualization. To understand how these letter-based relationships were working through and beyond the rubric of families and generations, I needed to look not at the content of the letters—traditional humanistic data—but at their metadata: the features of time, place, text, and material that define the dispersion rather than the integration of a social network, its gaps and distances as well as the words and feelings that constitute it.

Though still at the early stages of data collection, I hope that this digital project will contribute to a larger project on anonymous authorship and other non-generational models of literary production.

Fig. 3. Network Graph of Virginia Woolf’s Correspondence Networks

Topics

- Literary Letters

- Digital Prosopography

- Linked Open Metadata

- Sociology of Literature

- Queer Theory

Research Notes

-

“The Social Forms of Modernism: Visualizing Literary Sociability in Letters to Virginia Woolf”: poster presentation at MSA 16 (Brighton, UK)

-

“Close, Distant Social”: a blog post about the project, written for the Twentieth Century Literary Letters Project